Simple Metal Work

Metal tends to be a material with which you can do simpler repair work yourself. You can grind, solder, drill, saw, etc. metal. These are all tasks that are more or less impossible with glass or ceramics. Accordingly, there are also relatively many repairs that we can do ourselves on the metal parts of a lamp.

I have already mentioned one of the first metal jobs in an earlier section: sawing a rusted nut out of the threaded rod.

Another easy job is the fine sanding of the feet, in case all 4 feet of a 4-legged lamp are not exactly on one level, and the lamp therefore wobbles a bit when you tap it. As we know, this problem does not occur with 3-legged lamps. If you are lucky, the work is done by lightly sanding one foot. If you are unlucky, you have disturbed the exact vertical alignment of the lamp and it is now slightly crooked. Then you also have to sand the other feet until all 4 feet are perfectly flat and the lamp is still well upright. To check the evenness of the feet, I recommend using a thick, flat piece of glass of appropriate size as a base, which you have aligned absolutely horizontally. This is easily done with a spirit level. If a piece of glass is not available, you can also use a wooden board or any other object that is absolutely flat.

The inclined position of a lamp can be improved by first finding out where the lamp gets the misalignment. If it comes from the feet, you can easily improve it by sanding the feet accordingly. However, if it comes from another part, for example a slightly crooked column or thread, you can try to improve the misalignment by pushing small, thin brass plates into the joint. I know it is a game of patience, and not always successful, but you can always try. Otherwise, bent threaded parts etc. cannot be bent back without further ado. If the glass font sits crookedly because one has cemented its undermount crookedly, or if the burner sits crookedly because the font collar is not well horizontal (all this has happened several times!), there is not too much you can do about it. If, however, the inclined position is visually very disturbing, you can remove the crooked brass undermount or the font collar using the method described above and replace it with new parts, but now cemented in so carefully that the disturbing misalignment is well corrected. It will always happen that a lamp, especially a quite high column lamp, is slightly crooked. The best way to notice this is to turn such a lamp, complete with glass chimney, on a rotating stage around its vertical axis and observe how the upper part of the chimney performs a small pirouette. But there is nothing wrong with that. This is in the nature of a lamp that consists from bottom to top of many small parts that have been placed on top of each other.

Soldering or Gluing a Broken Zinc Cast Foot

A somewhat delicate and more difficult job is soldering a broken foot of cast zinc. Cast zinc is a brittle material that breaks easily if you give it a hard push or if you try to bend bent parts back. Three of my lamps arrived with freshly broken feet because the seller had packed them skimpily, and you could still see the marks of the impact very clearly in the box. Parcel shipping can sometimes be very rough. Soldering on correctly is difficult because the soldered-on foot has to have the same slope and height of the other feet, otherwise the lamp really gets a crooked vertical position. Now, try to align a small foot exactly so that it lies perfectly at the break edge on the one hand, and also has absolutely the same slant as the other feet on the other. This is a job where you really wish you had several hands....

There is still quite a danger lurking when you try to solder zinc castings. Zinc castings consist of an alloy of zinc with small amounts of lead, antimony, bismuth and other metals to make zinc very liquid and perfectly castable. But these additives lower the melting point of the alloy. And there is a real danger of making a real hole in the zinc part to be soldered with a very hot soldering gun instead of making a professional and permanent connection.

A more promising variant is to glue the broken foot instead of soldering it. In the meantime, there are extremely strong two-component adhesives that are excellently suited for such demanding, sometimes large-area gluing work. I have been working with the two-component adhesive Pattex® Stabilit Express for years. This adhesive sticks very firmly and permanently.

Whether the base is soldered or glued to the rest of the lamp, you have to make sure that the alignment is absolutely correct; otherwise the lamp will later stand at an angle. The correct alignment of the lamp and the base for soldering is a real game of patience; failed attempts are virtually pre-programmed. After 2-3 such attempts, I have reformed and switched to the glue option for good.

I do not attempt to glue a broken foot directly at the point of breakage, as the amount of glue remaining within the breakage would be very thin indeed to ensure excellent stability. I glue the foot to the otherwise invisible underside with a suitably cut and bent brass plate. Due to the generous dimensioning of this brass plate, you now really have a large gluing surface. The broken edge that is still visible at the top will disappear later through bronzing (see above for my method).

But even with this method, it is necessary to ensure perfect alignment of the parts to be glued. However, this work can be done much more easily here. I place the lamp without the burner upside down on the work table and make sure that it cannot fall over (the contact surface of the font collar could possibly be too small to provide stability for the lamp when placed upside down). I glue the broken foot with superglue at the place of breakage. After a few seconds, the superglue is solid. Now I can cut and bend the brass plate to be glued. With a good portion of the two-component glue, this brass plate is then glued under the foot. After drying, even protruding, disturbing residues can be sanded off with the Dremel® sanding attachments, if that is important to you.

Of course, I assumed with this method that the foot was only broken off, without any metal parts being bent or otherwise damaged. If parts are nevertheless bent and damaged, you can't get the superglue to help, otherwise the final glued foot will be crooked.

Now the only thing that helps is patient, sensitive sanding of the bent parts so that the distortions are no longer visible later. You have to lean the broken piece against the fracture again and again to see how much sanding is still necessary. The gluing is done differently than described above. First lay the lamp lengthwise on the table to fit a piece of sheet brass exactly under the base. Then glue the broken piece in place, wait 2-3 minutes (no longer!) until Stabilit has tightened a little, and now carefully place the lamp on a completely flat surface on its feet so that you can glue the broken foot exactly touching the base rather than crooked. Now you can quickly correct the foot part if necessary (press the brass piece firmly with your finger from below). It is advisable to hold the glued piece patiently for 5-6 minutes, otherwise it may come loose from the glue seam in the first few minutes when Stabilit is still reasonably flowable.

| My tip: Proper soldering is a matter of practice. Larger metal parts that are to be soldered together require strong soldering irons (from 100 W; 150 W is better) so that you can heat the larger metal mass properly, otherwise lead solder cannot bond permanently with the rest of the metal. The areas to be soldered should be finely ground so that the soldering acid can wet the actual metal. Surfaces that are not cleanly ground, tarnished, dirty, greasy or possibly coated with protective varnish will not accept solder. Attention! Zinc alloys are not completely heat-resistant, especially if their lead content is somewhat higher. Then it can happen that the zinc parts to be soldered melt themselves if you heat them with a very hot plunger. If you are not sure whether your lamp will tolerate strong soldering iron heat well, then you should carry out a test soldering on a completely invisible spot, deep inside the base, and also take great care that the resulting hole will not be visible, in case the zinc alloy at this spot cannot withstand the heat and melts away. If this happens, you should definitely change to a weaker soldering iron and use lower melting lead solder. |

Soldering or Gluing a Metal Crack

Further soldering or gluing is necessary for cracked brass sheets. Brass forms so-called "stress cracks" over time. They are often very fine like hairline cracks and not disturbing. However, they can also be continuous, with the result that the brass sheet is really cracked here and has come apart. This often happens in places where the brass mounting (e.g. the connector between the base and the column or vase) is under tension. If you want to repair such a spot, you have to solder (or glue; see above) a brass sheet cut in the right size and bent into the right shape to the crack all over from the inside. In order to keep the crack as closed as possible, the piece must be carefully pressed together with screw clamps or other aids. Before soldering or gluing, make absolutely sure that the brass sheet to be attached has the right bending shape and fits fairly well to the crack.

Gluing the brass sheet is done as described above, but without superglue, which is unnecessary here. For soldering, wet the entire soldering surface of the brass sheet with soldering acid as usual and apply a few drops of solder to it, then melt it and spread it over the entire surface. Press this completely soldered side against the crack and then heat the sheet by pressing the hot soldering iron on it for a long time. The solder layer melts and bonds with the brass of the cracked area, which of course you had previously wetted with soldering acid. This subsequent heating works even better with the Bunsen flame instead of the soldering iron. The more carefully you have shaped the brass sheet, the better the soldering or gluing will work. It is important that the soldering or gluing area is large enough, because later this part of the brass mounting will be under tension again when the lamp is assembled.

Soldering and gluing work on zinc and brass parts

Top row, from left: Soldered foot of lamp L.017 (bottom and top views)

Soldered foot of lamp L.101 (bottom and top view)

Bottom row, from left: Glued-on foot of lamp L.131 (bottom and top views)

Crack of the brass connector of lamp L.288 soldered from behind (pictures from outside and inside)

Repairing a Bent or Broken Vase

What I described above with the broken feet on cast zinc lamps, namely that the cast zinc is quite brittle and can break easily, may even happen on the vases of cast zinc lamps. There are many lamps whose vase and base parts are separated from each other only by a very narrow spot. This narrow connection between the two parts is of course particularly sensitive to impacts from outside. Four lamps in my collection came with damage to this narrow connecting area. One Wild & Wessel lamp (L.173) came from the UK with a considerable misalignment; it was neatly bent at this narrow joint. Three more lamps all of very slender shape but with a heavy stone base came with broken joints. These fractures were fresh, so the damage had occurred during transport.

If you refrain from making a claim or returning the lamp for known reasons (see Acquisition of Kerosene/Paraffin Lamps - Shipping and Insurance), you will have to repair the damage yourself. This can sometimes be quite tricky, because the repaired lamp has to be absolutely vertical again. I explain here how this can be done.

Straightening the strongly curved lamp L.173 by external force using hammer blows was out of the question, because that would damage the lamp even more. I had to saw it off at the narrowest bent part and separate the vase from the base. From here on, the procedures are the same for the broken base parts. Therefore, I describe the procedure in general for all similar cases.

First, I choose a thick, stable copper tube (available at all DIY stores) with a suitable diameter, cut it to a length that allows me to obtain a sufficient tube length in both the vase and the base part and glue this piece of tube first in the base part as vertically as possible and half of it protruding from the sawn area. For gluing, I use the inexpensive polyester filler Yachtcare KK-Plast VT mentioned earlier (see Working on Glass, Ceramics and Stones - Replacing and Recementing Font Collars or Brass Undermounts) or another adhesive with good strength, and apply it to fill the entire space between the tube and the zinc cast inner surface of the lamp. When doing this, make sure that no glue gets inside the tube so as not to block the passage of any threaded rod that may be needed. The length of the tube should be determined with care: it should neither obstruct the insertion of a font in the vase nor the attachment of a threaded rod under the base.

After the filler or glue has dried thoroughly, place the prepared base on a completely flat and absolutely horizontal level and repeat the gluing process with the vase part. After placing the vase on the base and holding it in this position with one hand, fill the space between the inner wall of the vase and the tube with a sufficient amount of freshly stirred filler or glue. This requires some skill, because the filler or glue must now be applied from above through the opening of the vase with a rather long spoon (be sure to prepare it beforehand and put it aside). It is advisable to work quickly at this stage, because the final, completely vertical alignment of the vase must be done before the glue is "tightened". The polyester filler mentioned needs 5-10 minutes to set. During this time, you have to use a good spirit level to ensure that the top edge of the lamp vase is perfectly horizontal (to do this, place the spirit level in different places and at different angles) and hold the vase in this position until the glue has set. That's why I like to use this filler, because it sets in a relatively short time. Pattex® Stabilit would also be very suitable as an adhesive, but it is simply too expensive for the amount to be applied.

After drying, the gluing seam must be cleaned from the outside by carefully sanding off any filler or glue residue. The more carefully and finely you sand this spot, the less noticeable it will be later, after you have finally bronzed the spot.

In the following picture I show the straightening of the crooked lamp L.173 with this method. The hand-drawn diagram at the bottom right shows the described gluing work with a metal tube (the tube is drawn in red, the glue in green).

The straightening of a very crooked lamp (L.173) at the narrowest point

From left: Crooked position of the lamp - After straightening - The glued narrow spot sanded - Scheme of gluing with an inner tube

The three other lamps in the collection that were repaired in this way (the broken area is marked with an arrow):

Three zinc cast lamps that were cracked or broken at the narrowest point

Repairing the Broken or Bent Edges

Sometimes you get a cast zinc lamp whose vase is broken at the top edge, probably because it was accidentally dropped from some height. Even worse are the bent edges of the cast zinc lid, probably for similar reasons. This is what happened to me with a stately, large lamp (L.246) whose vase was broken on two opposite edges and whose lid was significantly bent downwards in one place.

I first had to remove the broken edges completely from the fracture and shape them back into the right curvature by sanding and bending. Then I glued these parts with Pattex® Stabilit and carefully sanded them flat after drying. Great care is needed when shaping back the curved edge on the font lid. Cast zinc cannot be bent back like brass; it is quite brittle. You have to bring the bent area back into shape with hammer blows. In doing so, you run the risk of cracking the glass font. This work requires a lot of skill and care.

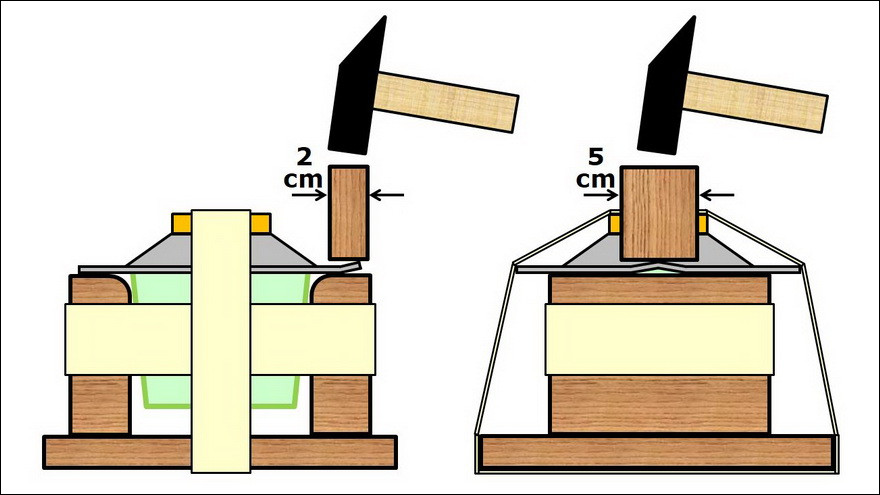

In the next picture I show schematically how I have always carried out this delicate work with success so far. I place the glass font with the bent metal rim made of cast zinc, brass, etc. on two stable, relatively thick pieces of wood (preferably pieces of laminate-coated kitchen worktops whose surface is quite hard) so that the glass does not touch the floor underneath. The area to be straightened must lie on one of these pieces of wood. I fix the font together with the pieces of wood on a stable worktop with thick adhesive tape (painter's masking tape is best) both horizontally and vertically so that they cannot move. Now I hold another piece of wood, about 2 cm thick and about 5 cm wide, with the end grain facing the bent metal, exactly on the bent spot and hit it carefully with a medium-sized hammer. It will be necessary to hit the hammer several times until the bent edge is straight again. It may happen that the zinc edge gets a crack during this work, but this can be filled up again after the work is done.

Diagrams for straightening a bent edge (shown from two different viewing axes)

For other types of bent edges, e.g. at the top rim of a vase or the bottom of a pedestal, you have to think up and build appropriate constructions. In any case, a little inventive talent and the ability to combine are required.

You can see the result of these explanations in the next photo. After careful straightening, filling, sanding and bronzing, there is nothing left of the original damage to lamp L.246 (see arrows).

Repaired or corrected bent edges on lamp L.246

Top row, from left: Broken edges in two places

The bent part of the font lid

Bottom row, from left: Top view after the broken edges have been removed

Top view with glued and sanded edge pieces

Final result without the repairs visible (see arrows)

Modelling of Missing Small Parts

An unusual repair job that I would like to introduce to you is the modelling of missing small parts with Pattex® Stabilit Express. However, this work requires craftsmanship, because now you have to remodel the missing piece on the spot, shape it, sand it to the right shape and size if necessary, flatten it and then paint over it with matching paint. As I mentioned above, solidified Stabilit mass can be worked like a metal. The adhesive seam is so strong that it will not break off during this work.

As a first example, I take the right hand of the figure of my sculptural lamp L.077. When I bought the lamp at an auction, the metal font carrier in her right hand, in which the glass font was cemented, was soldered on so badly and crookedly that I had to remove it from the soldering point and re-solder it. In the process, exactly what I described above as a possible danger when soldering zinc parts happened: half of the hand with the fingers literally melted away! There was no other option but to recreate this missing part with modelling clay. I used Stabilit Express for this. To do this, I applied a sufficiently large mass of Stabilit Express to the remaining half of the hand, let it set properly, and then removed layer after layer of material until the hand was well modelled. Finally, I painted over the newly acquired hand with matching colours. It is logical that this small "sculpting work" requires small and smallest milling attachments. These mini milling cutters are available from both Proxxon® and Dremel® in DIY stores. It is also understandable that certain artistic skills must be present.

Newly modelled hand at lamp L.077

Top row, from left: The complicated set-up for the difficult soldering work ahead

Zinc part finally soldered; the four fingers have melted away

The still existing back of the figure's hand

Bottom row, from left: All the fingers have been reshaped with Stabilit; the hand now holds a self-designed fantasy grip

The fingers are painted with Revell colours

Final state of repair: The glass font is now completely upright

Two further examples show that the addition of a broken and lost metal ornament is quite possible if one only wants to and dares to. On a high-quality cast zinc lamp, a small ornamental piece was missing from one of the three lion paws (see arrow). To create a permanent connection, I glued a piece of brass cut to size with Stabilit. I applied enough filler compound to the front to form the missing ornament. Bronzing is done as with all zinc castings: first prime with shoe polish and then apply the gold wax.

Newly modelled ornamental part on lamp L.150

Top row, from left: The missing ornament clearly visible in the first photo

The dismantled and cleaned foot with the incomplete end

The glued brass piece from behind

Bottom row, from left: The glued-on brass piece in front view

Filler compound applied and modelled accordingly

Final state of the repair: foot piece now complete again

A very similar repair work was also necessary on an old Ditmar lamp. Here, a larger side ornament of the base had broken off (see arrow). Here, too, I glued on a piece of brass that had been sawn off accordingly. After filling and modelling the Stabilit, it was only necessary to bronze it. It is now impossible to see the repair from above.

Newly modelled side part at the base of lamp L.349

Top row, from the left: The broken off part of the base clearly visible from below

Glued brass piece seen from above

The glued part of the brass piece seen from below (recess for Ditmar's logo)

Bottom row, from the left: Stabilit applied and the grooves milled on it

Base in final, bronzed state

Top view (which part is my addition?)